The Moss Landing Whaling Station's First Whale, January 1919. A crowd has gathered to watch the first whale, a sperm, be hauled up the slipway. The whale is visible floating in the left foreground.

The Moss Landing Whaling Station - 1919-1926

Early Shore Whaling in Monterey Bay

Commercial shore whaling in Monterey Bay began in 1853 when John Pope Davenport set up his try-pots near Monterey, and with a crew of Azorean whalemen, began killing and processing whales for their blubber. The blubber was boiled at shore-side procession stations and rendered into oil that was the primary sources of light.

However, in the face of a new petroleum product known as kerosene, the price of whale oil dropped steadily during the late 1860s and 1870s, and by 1886, the shore whaling industry in the Monterey Bay Region was over. Contrary to what many historians and naturalists often declare, the region's shore whaling ended because whale oil became obsolete, not because the whale population was depleted.

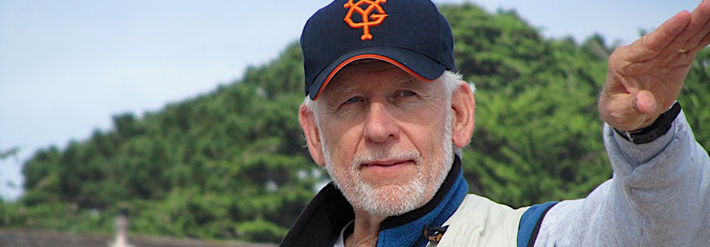

Captain Frederick Dedrick. Born in Norway and trained in the Norwegian whaling industry, Captain Dedrick was the manager of the Moss Landing factory.

Modern Shore Whaling

With invention of the harpoon cannon, and the development of steam-driven chase boats and processing plants, a new, modern whaling industry came into the Pacific in the early 20th century. In 1914, the California Sea Products Company was incorporated in California, and Captain Frederick Dedrick, a Norwegian whaling expert, selected a site at Moss Landing to build a large whaling factory. The plant had two steam-driven chase boats, each with a harpoon cannon mounted on its bow.

Moss Landing Whaling

Slowed by the advent of World War I, the plant did not open until late 1918. In January 1919, the chase boat Hercules towed in its first catch, a large sperm whale. The news that a whale was being towed in to the plant to be processed attracted several hundred spectators. During the company's first year of operation the arrival of a whale continued to bring out crowds. However, the stench of the processing plant was often so great that it caused many of the spectators to vomit. (When a southeast wind blew down the Salinas Valley and across the bay, the odor of whale was strong as far away as Santa Cruz.)

This modern shore whaling not only processed the blubber into oil (used by soap manufacturers), but also cooked the meat and turned it into chicken feed, and ground the bones into bone meal. The whaling company used every part of the whale.

The only remnant of the Moss Landing whaling station is this pile of boulders that was placed here in 1917 to anchor the end of the whaling station slipway. During low tides, they emerge to remind us of the whaling history on this spot.

The next two years saw the advent of something of a whaling boom along the California coast. And, where the 19th shore whalers had not caught enough whales to threaten their population, these twentieth century factories literally ground up the population. By 1924, the whales were becoming extremely difficult to catch both because they had learned to avoid the immediate coastline, and because their numbers were dropping.

In 1926, the Moss Landing whaling station operated only briefly, and by 1927, the factory was closed. The machinery was removed, and the building fell into disrepair. Captain Dedrick continued to pursue his whaling career, but using processing ships in the open ocean, rather than shore stations.

Moss Landing today, looking north. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute building are on the left, and the boulders that marked the ocean end of the whale station slipway are in the distance on the left.

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

In the early 1990s, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (known by its initials - MBARI) began building several large research centers on the site of the old whaling factory. Considering MBARI's research interests in replenishing and protecting the ocean's resources, it is extremely ironic that such an operation was located on the site where hundreds of whales had been sliced up and turned into chicken feed and bath soap.

The only remaining vestige of the whaling factory is a pile of boulders that anchored the bottom of the slipway where it rested on the sand. During low wintertime tides, the rocks emerge to remind us of the bay's little known whaling history.

Sources: The most complete and current account of California Shore Whaling can be found in the Maritime Museum of San Diego's journal titled Mains'l Haul, Vol. 37, No. 1, Winter 2001. The authors in this journal include Ronald May, Georgia Fox, Sandy Lydon, and Robert Lloyd Webb. Contact the journal's editor for information concerning availability of the journal: Mark Allen, editor@sdmaritime.com