Drawing of a steer dying on the plains by Charles Russell. Note coyotes waiting in the wings. This scene was played out thousands of times in California during the drought of 1863-1864.

Drought History Segment III

1863-1864 –The Drought of Fat, Waddling Buzzards

Note: For earlier drought stories see:

I – The Screaming Horses drought – 1840-41

II - The Lynching Drought – 1855-56

The 1860s – The End of Pastoral California

The winter of 1860-61 saw a couple of good storms and enough rain fell in February in the upper San Lorenzo to blow out Isaac Graham's dam and flood the lower parts of Santa Cruz for a time. But the extremes seemed to be leveling out, and attentions were quickly diverted by the attack on Fort Sumter in April, 1861 and the onset of Civil War.

And then it started:A Natural Disaster Smackdown. It's a wonder there was anyone living around here by the end of the 1860s. In its bare bones, with the US Civil War and Lincoln's assassination as the backdrop we have an astonishing sequence of disasters: The Flood of 1862, The Drought of 1863-1864, Wildfires of 1865, two large earthquakes and a Smallpox epidemic to finish off the decade.

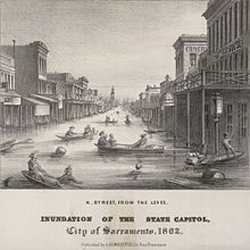

Image of Sacramento during the flood of 1862

The Mother of All Floods – 1861-1862

We're here in the 1860s to re-visit the drought, but we absolutely must spend a minute with the flood that preceded it. This wasn't just any flood. It scarred California's memory so deeply that in 2011, the United States Geological Survey declared it to be the biggest flood event in California's written history. 43 days of rain turned California's valleys into lakes, rivers tore entire town away and killed hundreds of thousands of cattle. The USGS has named it the ARKstorm Scenario – the plume of subtropical moisture swung up like a firehose and locked onto the Pacific Coast.

With the rain hammering on the roof, Californians huddled in their churches and prayed for the rain to stop. When it finally did in late January 1862, bridges were gone, and the state was left with a huge bathtub ring of mud, and no funds. California was bankrupt.

We'll come back to the flood of '62 and the huge effects it had on the Monterey Bay Region sometime, but for now, just imagine the locals digging out of the sand and mud, relieved that the hills were turning green for the remaining livestock that hadn't been swept away into the ocean.

Then, once everyone was busy building levees and organizing to protect their properties from future floods, it stopped raining altogether. Again.

The buzzards (more correctly termed turkey vultures) grew so fat during the 1863-1864 drought that they could only waddle.

THE DROUGHT OF 1863-1864

When it didn't rain that much in the winter of 1862-1863, locals couldn't believe that the natural order had turned off the faucet, so they called that first winter a "dry spell." Yet, a mere 22 months after the '62 flood waters began to recede; churches were filled with congregations praying for rain.

Once again, the sun had baked the earth, the grass shriveled and the cattle bellowed and died "as if they were poisoned." An article in a Monterey newspaper in the summer of 1864 suggested that the rancheros should ride out and kill the cattle to "prevent them from dying." Killing was much more humane than a slow death in a dry water hole. Grizzly bears and coyotes were in heaven, and the buzzards got so fat they could only waddle.

Most California historians conclude that the drought of 1863-1864 was a major turning point in the state's history, marking the end of the dominance of the old, Spanish-Mexican style pastoral economy. It also marked the end for many of the Californio rancheros who had survived the drought and race war of the 1850s, and the mega-flood of '62.

Profiting from the Drought

Some entrepreneurs turned the drought to their advantage, most notably, German immigrant Henry Miller, and recently-arrived New Englander, Loren Coburn. Coburn owned large ranches in both present-day coastal San Mateo County (he owned Pigeon Point, for example) and Monterey County. When his Monterey County pasturage withered away, he drove those herds north into the foothills behind Pescadero where the effects of the drought weren't so severe. Once the price of beef recovered he drove them to San Francisco and enhanced his fortune.

Henry Miller was one of a few cattle ranchers able to survive and even thrive during the 1863-1864 drought by moving his cattle to his pasturage he owned beyond the reach of the drought.

Henry Miller also had far-flung properties across the West, and during the drought he bought cattle for $2 a head and then drove them to his northern properties and sold them in San

Francisco in 1865 for $70 apiece.

One person's drought is another's opportunity.

Santa Cruz County's lumber industry was also hit hard by the 1863-1864 drought. The southern slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains had always relied on its dependable year-round streams to drive Santa Cruz's factories and mills. But without the winter rains to maintain the stream flows, the rivers dropped until they could no longer drive the wheels or fill the flumes. By the fall of 1864, for the first time in local memory, lumber was being shipped into Santa Cruz County.

Wildfires – 1865

Locals were not surprised by the wildfires that roared around the Monterey Bay Region in fall of 1865--fires always followed drought. The forests were tinder dry, and with so few residents or developed property in the mountains, fire suppression was usually left to the affected property owners and was meager at best. In September of 1865, after two winters of low rainfall, Monterey Bay was covered by huge clouds of smoke as the forests burned. For most of September, the hills behind Monterey and their signature Monterey pine trees were on fire. Monterey County landowner David Jacks lost thousands of dollars worth of forest and pasturage. At the same time, the Santa Cruz Mountains were also on fire with the local newspaper declaring that the "loss of timber will prove immense."

Earthquakes – 1865 & 1868

At thirteen minutes before 1:00 o'clock on the afternoon of October 8, 1865, the Santa Cruz Mountains were shaken by a 6.5 earthquake that was felt from San Juan Bautista on the southeast to Napa on the north. Modern seismologists put the earthquake's epicenter somewhere in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Damage was relatively light, though the temblor drove many of San Francisco's residents out into the streets. A Santa Cruz County newspaper suggested that the quake was caused by geological flatulence.

One of the interesting consequences of that earthquake was the increased flow of streams throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains. Flouring and lumber mills that had closed during the drought were able to immediately resume operations without any rainfall.

A graphic depiction of the October earthquake in San Francisco.

Bam! Another Earthquake

The October 21 1868 earthquake had an estimated magnitude of 6.8 with an epicenter in the East Bay along what is now known as the Hayward Fault. It killed thirty San Franciscans, and did considerable damage throughout the East Bay, but damage was relatively light in the Monterey Bay Region.

The Final 1860s Smackdown

We can forgive the good people of the region in the late 1860s if they concluded that they were being punished. Just as the rumble of the October earthquake died away, a warning came out of San Juan Bautista that a smallpox epidemic had erupted. (The 1868 smallpox epidemic was a global event.) Despite quarantines and even the burning of a bridge to stop east-west traffic, by the end of the year, hundreds in the region had perished and many more had fled to the hills before the epidemic had run its course.

Living here is risky business

By the end of the 1860s, those who had lived here and survived that many-splendored gauntlet understood that living here involved a risk. Continual and ever-changing risk. They tried hard to understand the causes, but they knew that their "normal" included flood, drought, and earthquakes, with a helping of wildfire and even pestilence thrown in. There was a strong sense of humility.

Drought was (and is) one of the prices charged for living in this splendid place. Drought is the elephant that never leaves the room. Along with his nasty siblings, flood and earthquake, they tag team the region, smacking us upside the head now and then to teach us a basic lesson in humility. Communities could prepare for flood (organizing and building levees), and earthquakes (building stronger structures and staying off "made land"), but drought was a different matter.

Maybe that's always been the problem. Instead of preparing for a drought, they should have learned how to live with drought and invited him to sit permanently at the head of the table. That way they would never have forgotten he lived here.

Note: UCSC Professor Gary Griggs and I will be hosting several events in mid-October to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Loma Prieta Earthquake. With a field trip, and an illustrated lecture-show we hope to revive that feeling of helplessness and awe that we felt on the evening of October 17. And to remind that earthquakes are a part of normal too.

The Final 1860s Smackdown

We can forgive the good people of the region in the late 1860s if they concluded that they were being punished. Just as the rumble of the October earthquake died away, a warning came out of San Juan Bautista that a smallpox epidemic had erupted. (The 1868 smallpox epidemic was a global event.) Despite quarantines and even the burning of a bridge to stop east-west traffic, by the end of the year, hundreds in the region had perished and many more had fled to the hills before the epidemic had run its course.

Living here is risky business

By the end of the 1860s, those who had lived here and survived that many-splendored gauntlet understood that living here involved a risk. Continual and ever-changing risk. They tried hard to understand the causes, but they knew that their "normal" included flood, drought, and earthquakes, with a helping of wildfire and even pestilence thrown in. There was a strong sense of humility.

Drought was (and is) one of the prices charged for living in this splendid place. Drought is the elephant that never leaves the room. Along with his nasty siblings, flood and earthquake, they tag team the region, smacking us upside the head now and then to teach us a basic lesson in humility. Communities could prepare for flood (organizing and building levees), and earthquakes (building stronger structures and staying off "made land"), but drought was a different matter.

Maybe that's always been the problem. Instead of preparing for a drought, they should have learned how to live with drought and invited him to sit permanently at the head of the table. That way they would never have forgotten he lived here.

Note: UCSC Professor Gary Griggs and I will be hosting several events in mid-October to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Loma Prieta Earthquake. With a field trip, and an illustrated lecture-show we hope to revive that feeling of helplessness and awe that we felt on the evening of October 17. And to remind that earthquakes are a part of normal too.