SERIOUS DROUGHT - HELP SAVE WATER.

Monterey Bay Region Drought History Part I

Beyond the Rain Gauges

Early Droughts

It's official. On January 17, Governor Brown declared it so, and in mid-February he stood grim- faced in the San Joaquin Valley dust with President Obama nodding his head in agreement. Were that not enough, the drought has now climbed up onto the signs above Highway 1 usually reserved for capturing kidnappers and drunk drivers. I saw the brake lights ahead before I could read the sign as startled drivers slowed to read the entire message (I'll withhold comment about reading speeds and the effects such signs have on traffic flow).

The Old Timer

You might wonder how folks around here knew they were in a drought before highway signs were available to shout it or television could broadcast images of politicians standing in dusty fields looking all worried and serious, or TV weather anchors showed satellite images of a storm track carrying that winter rain northward to places that don't need it.

Back in the olden days residents of this region didn't need to be told. They could feel it, see it and hear it. Those who had been here awhile weren't surprised. If you were a newcomer there was always someone around who had been here longer – we'll call him The Old Timer – who would say, "Yup. This here's a drought. We get them all the time. You think this one's bad? You shoulda seen the one in…" and then he would remind of 1857, 1864, 1877, 1898.

Then, the Old Timer would be put away until the next natural calamity.

Drought. The Elephant that Never Leaves the Room.

First off, if you're looking for some precision in this drought business, you'll be disappointed. The definitions are general and have little to do with rain gauges. Basically, as one Australian website states , "it is a dry period when there is not enough water for users' normal needs." The California Department of Water Resources admits that "there are many ways that drought can be defined," and then goes on to describe those many ways. Those definitions all agree: it's all about what happens to people.

It's not tied to rainfall, necessarily. It all depends on where you are and the impact a water shortage has on you.

Since 1769 Euro Americans first came into this region and began writing accounts, the typical California straight line record of fecundity and prosperity was punctuated by a steady stream of natural calamities, most of which were easily identifiable – floods, earthquakes, wildfires, and windstorms. All those were easy to recognize.

Droughts were harder. They began slowly, often punctuated by episodic early-season showers (I call them "teasers"), and then the dry days tightened from south to north, with those living and working in the upper Salinas and San Benito watersheds feeling them first. The mid-autumn grass emerged and then withered and the hills stayed a tawny brown all winter. Stream flows fell. And then an endless parade of bright, cloudless days stretched on for months, shriveling the place.

Eventually, the blessed sound of steady rain on the roof would signal the drought's end, and a feeling of relief washed the drought memory away.

As John Steinbeck wrote in East of Eden about the Salinas Valley: "But there were dry years too, and they put a terror on the valley. They came in a thirty-year cycle…and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years. It was always that way."

Father Junipero Serra was confronted with all manner of new climatic challenges after his arrival in the Monterey Bay Region in June of 1770. Drought was one of them

Early Droughts – The Great Famine – 1770-1772

The Franciscans who came here to establish their missions had never encountered a climate quite like this one; it took them years of trial and error to figure out how to extract a living from the region's landscape. Father Junipero Serra, for example, had spent his entire New World career in Mexico, and the first thing he noted in June of 1770 when his mission was located on the north side of the Peninsula was the cold. That summertime Monterey fog.

After he was able to warm up a bit by moving his mission over the hill to the banks of the Rio Carmelo, he encountered something a bit more challenging – a drought. There was plenty of water in the river down below the mission, but no way to get it up on the alluvial terraces. By necessity, the Franciscans were the region's first dry farmers, planting their meager crops in the hope that it might rain. But they weren't familiar with the region's dry summers. Their early plantings shriveled and by the summer of 1772, Serra declared their puny garden "miserable." In a letter to Mexico in 1772, he admitted that: "We are starving."

Serra's only recourse was to release the few Indians living at the mission so that they might return to their villages and hunt and forage as before. They brought back enough venison and pine nuts and other local delicacies to see the Spaniards through the drought. (The ultimate solution at Carmel and many of the other mission was irrigation, but it wasn't until 1781 that a canal was completed that diverted the water of the Carmelo up onto the terrace where it could be used.)

In order to dramatize the early droughts for his TV viewers, Sandy used this skull on the nightly news to get the public's attention.

The Cattle on a Thousand Hills – the Droughts of the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s

Over the decades the mission herds of cattle, sheep and horses grew and wandered across the hills much to the delight of mountain lions and grizzly bears. Irrigation solved some of the missions' farming challenges, but the herds were dependent on the grasses that were dependent on the rains. In the early 1820s, the accounts tell of a drought that caused the livestock to "suffer dreadfully." Thousands of cattle and horses died of starvation out on the range. Cattle had more value than horses, and according to the accounts, the missionaries at Soledad took matters into their own hands and slaughtered 6,000 horses to release the pressure on the few surviving cattle.

There were stories of missionaries driving herds of wild horses over cliffs and into the sea during dry years to manage the grasslands.

Some droughts stuck in local memory longer than others – everyone that was here remembered the twenty months from 1828-1830 when the countryside was baked in the relentless sun. Watering holes dried up, stream flows dropped and the cattle and horses died by the thousands. Buzzards grew so fat they couldn't fly. This 1828-1830 drought also had other consequences – a sharp rise in lawlessness, as horse thieves roamed the countryside, stealing the few remaining broken horses. Rancheros went into debt to the ever-increasing numbers of foreigners moving into Alta California, and subsequent droughts often resulted in the Californios losing their land.

This Joe Mora drawing captures the violence that resulted against the wild horses during a drought in the region in the early 1840s.

But, the account of a drought in the early 1840s as retold by the artist and historian Joe Mora was the one that stuck with me. Again the issue was the herds of wild, unbranded horses competing with the cattle for scarce rangeland resources. The Alta California government ordered that makeshift corrals be built and all the horses, tame and wild, be driven in. The vaqueros then rode into the corral, separated the healthy, branded horses and released them until only the wild ones remained. The mounted vaqueros then formed a double file at the corral's gate and as the doomed horses were driven out, the vaqueros rode alongside and drove their lances into their hearts.

No one who witnessed the slaughter ever forgot it, the screams of the horses forever etched into their drought memory.

Every major drought in the region left a unique signature.

My next newsletter will discuss the two most memorable droughts of the 1850s and 1860s.

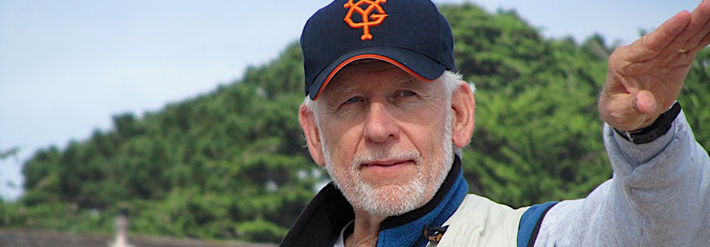

Sandy Lydon (left), Kirstie Wilde and Craig Kilborn, KCBA Fox 35 News Anchors, August, 1990. Sandy was the Weather Anchor during a drought.

Disclaimer Alert – Weather Dude

I need to divulge that during 1990-1991 I was the Weather Anchor at KCBA, Channel 35. Yea, right smack in the middle of the drought of 1987-1992. I got to hone my weather chops every night by looking into the camera and delivering the tiresome forecast: Nope. No Rain in Sight. I brought an old cow skull in and set it on the desk and played the role of the Old Timer. "You think this is bad? You should have seen the one that killed the cattle industry back in 1864…"

People would stop me and ask, "When's it gonna rain, Weather Dude?" I wanted so much to be able to say, "Look Out! Pineapple Express headed this way! Batten down the hatches!" But I couldn't. We'd go out hunting for weather news and all I could hear was the sound of pumps sucking air. Farmers were happy to stand in the dust and do an interview, but they would quietly ask us not to mention the part about their pumps and that the water table was dropping like a stone.

It was then that I began to learn how subtle and complicated droughts really are.

People would stop me and ask, "When's it gonna rain, Weather Dude?" I wanted so much to be able to say, "Look Out! Pineapple Express headed this way! Batten down the hatches!" But I couldn't. We'd go out hunting for weather news and all I could hear was the sound of pumps sucking air. Farmers were happy to stand in the dust and do an interview, but they would quietly ask us not to mention the part about their pumps and that the water table was dropping like a stone.

It was then that I began to learn how subtle and complicated droughts really are.