Drivers rarely notice the huge wall that rises up on the ocean side as Highway 1 drops down into the valley just north of Davenport. What the heck's going on here? And, isn't there a creek down in that valley somewhere?

Are those Real or Fake?

The Mysterious Ramparts on Santa Cruz County'sNorth Coast

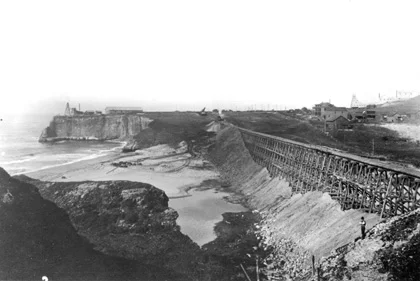

Sometimes an object is so large that we never notice it. We may pass by it for a lifetime and never realize that it's there. Such is the case of what I like to call the North Coast Railroad Ramparts. It was not until recently that I began to notice the huge, wide earthen mounds that carry the railroad tracks across each coastal stream between Santa Cruz and Davenport. Study the above photograph. It was taken while standing on the southern end of San Vicente Beach looking north toward Davenport. In the distance on the right you can see the tall white stacks that mark the Lonestar Davenport Cement plant. And, notice the very level wall on the right. That's the rampart.

Looking north toward Davenport across San Vicente Beach. The dam-looking structure on the right is the railroad rampart that carried Union Pacific trains to Davenport.

Highway 1 looking north toward Davenport. Note the straight, flat line atop the bank on the left. That's the railroad grade atop the Rampart. Both the rampart and the fill upon which Highway 1 was built are artificial. The original grade of San Vicente Creek is well below both of them.

The second photograph is the view you usually see while driving Highway 1 toward Davenport. Because you are intent on your driving, you don't notice that, as you drop down into the valley cut by San Vicente Creek, the wall on your left blocks your view of the ocean. This pattern is repeated all along the stretch of highway from Santa Cruz to Davenport. The railroad line that runs between present-day Highway 1 and the ocean blocks each and every coastal stream.

The story of the Ocean Shore Railroad Ramparts

In 1905, after years of discussions about a possible coastline railroad between Santa Cruz and San Francisco, the Ocean Shore Electric Railway began building a line south from San Francisco and north from Santa Cruz. When completed, the planned railroad would have two standard gauge electric lines running side by side, shuttling passengers and freight along the coast and opening it up to dependable transportation for the first time. Meanwhile, almost simultaneously, the Southern Pacific Railroad announced that it too would be building a railroad line along the coast north from Santa Cruz. The two railroads cooperated in designing trestles and cuts that would eventually accommodate three (3!) broad gauge railroad lines running side by side.

One of the primary sources of freight for the railroads was to be the carloads of cement that would be shipped from the under-construction Santa Cruz Portland cement plant on the north side of San Vicente Creek. Because of the extreme weight of the intended freight, the railroad construction engineers determined that wooden trestles could not bear the huge weight of loaded trains, so they decided to build temporary trestles at each stream crossing and then immediately fill them in. The fill material was readily available from the huge cuts necessary to level out the grade on either side of each valley.

The San Vicente Creek trestle being filled in, 1906. If you look closely you can see the fledgling cement plant in the distance on the right. So, the first thing you should remember is that inside each of those ramparts is the skeleton of the trestle that was buried almost a century ago. The trestles were built first to provide a framework for the fill material, helping to contain the materials when they were dumped as well as guiding the pile with a uniform slope on either side. Besides, imagine how difficult it would be to get the materials from each side of the canyon to the middle without the trestle from which to dump it.

Eventually only two sets of track were laid atop these ramparts, one for the Ocean Shore Railroad and one for the Southern Pacific. The Ocean Shore went out of business in 1923, and today, there is but one set of rails atop the ramparts, operated now by the Union Pacific Railroad.

Perhaps even more ingenious than the ramparts was the way that the engineers solved the problem of allowing each of the creeks to flow past these huge earthen dams. Rather than put culverts down and then cover them with the fill material, railroad workers drilled a tunnel on the north side of each valley to allow the streams to flow out to sea. So, each creek wandered up to the rampart, turned right and followed its base until reaching a tunnel that then carried it out to the beach.

Several observers in 1906 wondered aloud whether or not the tunnels would be of sufficient size to carry the water from heavy winter storms, but despite the huge rains of such flood events as Christmas 1955 or January 1982, the tunnels have proved to be large enough to handle the flow.

The exit tunnel for San Vicente Creek at the beach. The creek flows directly into the ocean behind the photographer. Before the construction of the cement plant, and this railroad rampart/tunnel system, San Vicente Creek was considered to be the best trout-fishing stream in Santa Cruz County.

What happened to the creeks?

The social and cultural impact of the ramparts

Many North Coast residents bemoaned the creation of the ramparts in 1906 and the way that they blocked their access to the ocean beaches. However, the ramparts were actually huge screens, blocking the beaches from public view. Beginning in the 1950s (and accelerating in the 1960s), these "secret" beaches became havens for folks wishing to sunbathe and cavort in the nude. Today, almost a century after the ramparts were built, they provide privacy for nude sunbathers and homeless communities along the coast south of Davenport.

All of this does relate to railroads, indirectly, as locomotive engineers who operate between Santa Cruz and Davenport often slow and sometimes even come to a stop on sunny days to enjoy the view.

The Lesser Ramparts of Highway 1

When the State of California began straightening out the extremely crooked and dangerous Coast Highway in the 1930s, their engineers decided to echo the railroad ramparts that were already there. So, in each of the major valleys, they laid shorter roadbeds upon which to build the highway.

The two ramparts of San Vicente Creek at Davenport. The straight line on the upper left is the Railroad Rampart, while the lower rampart of Highway 1 and its stream of cars is just below it. Imagine if the San Vicente tunnel were blocked, the resulting lake would flood the highway and all of the buildings in the center of the photograph.

All of this raises once again the question of how did they make certain that San Vicente Creek could exit to the ocean during heavy rains? The highway engineers merely built culverts that extended the tunnels upstream so that the creeks continued to make their right turn, slide along the face of the new, highway rampart, into the new extended tunnel and out to sea.

Sources: The history of the Ocean Shore Railroad and Southern Pacific can be found in The Last Whistle by Jack Wagner, published in 1974, and Ric Hamman's California Central Coast Railways, 1980, soon to be republished by Otter B. Press.